|

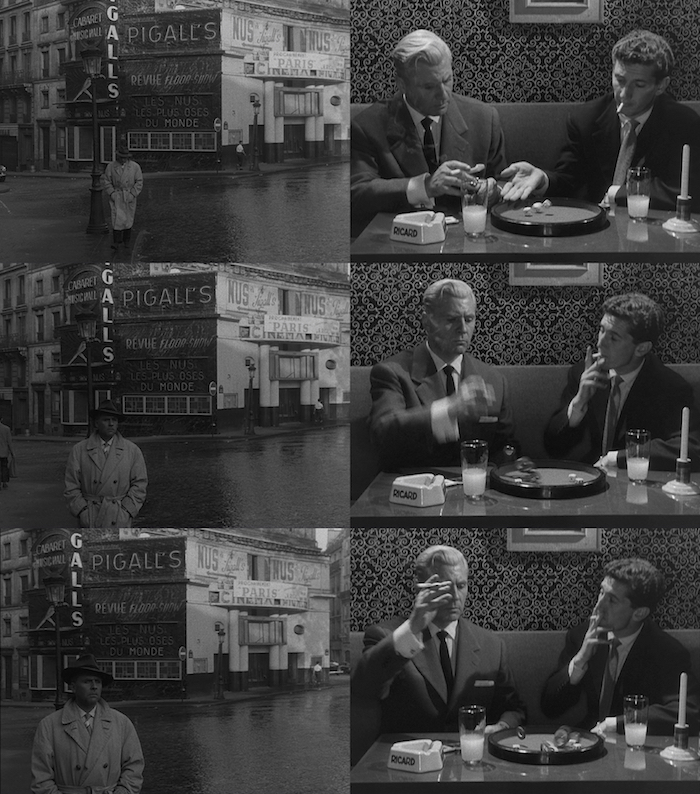

| A Nazi soliloquizes to silent listeners in Melville's debut. |

Le Silence de la mer - The Silence of the Sea (1949)

Dir. Jean-Pierre Melville

Nvl. Vercors (Jean Bruder)

Starring: Howard Vernon, Nicole Stéphane, Jean-Marie Robain

Review By Greg Klymkiw

There are many forms of resistance during an occupation. As Jean-Pierre Melville's debut feature film proves, the most powerful of all is silence. When an old man (Jean-Marie Robain) and his niece (Nicole Stéphane) are forced to billet Nazi officer Werner von Ebrennac (Howard Vernon) in their own home, they choose to contribute to the French resistance of German occupation by going about their lives as if their unwelcome guest doesn't exist.

Silence proves to be a formidable weapon. Le Silence de la mer is based on the secretly published novel by Jean Bruder under the nom-de-plume "Vercors", published and circulated in France during the Occupation. So horrific is the power of Melville's adaptation that the film succeeds as one of the most chilling anti-war films ever made and this from a picture that seldom leaves the confines of a cozy, bourgeois country living-room. What a gloriously mad first feature film, but one that radiates the sheer abundant cinematic glory that is Jean-Pierre Melville.

The first two-thirds of the movie involves the old man and his niece sitting quietly - the old man reading and/or smoking his pipe whilst his niece intensely embroiders. The Nazi officer pays them nightly visits. He acknowledges and respects their resistance, their cold, borderline cruel silence.

Still, this does not deter him from trying to establish a human connection. He wanders about the living-room, speaking in soliloquy. His words are always gentle, mannered and cultured. It doesn't take long to figure out he isn't the usual garden variety Nazi Officer. It seems that Werner von Ebrennac has the soul of an artist and he holds a deep love and admiration for French culture.

Many of his monologues are heart-achingly beautiful observations on art, language, music and literature. He even reveals tidbits about his life in Germany, some very personal. When he tells the story about his one great love and how he was eventually driven from her when she displayed a deep-seeded cruelty he could have never before imagined, we are allowed to see the pain and disappointment in his eyes. We are allowed to feel for him as a human being. His hosts, however, remain unmoved - at least on the surface. No matter what he says, the old man and his niece remain impassive - and, silent.

Their silence does indeed border on cruelty, though our Nazi doesn't see it that way. He acknowledges their right to silence. Astonishingly he seems to welcome it as the right of any countryman to resist their occupation at the hands of an enemy.

He occasionally veers into political territory - dangerous territory indeed since he betrays considerable naiveté and in so doing he attempts to provide a perverse justification for Germany's occupation of France. This eventually proves to be his biggest mistake because eventually he comes face-to-face with the true reality of his country's motives, their final solution.

Eventually a word will indeed be spoken from the "resistance". When it comes, it's excruciatingly painful. I personally find myself gasping and on the verge of weeping every time I experience this moment.

There's something so perfect, so indelible about this motion picture. Melville, a French Jew who was a resistance fighter during WWII, made this film not long after the war. Given the horror, danger and cruelty he experienced, one might have expected a very different film on his feature debut, but no, he is, after all Jean-Pierre Melville. Le Silence de la mer seems to set the stage perfectly for the compassion and humanity he displayed throughout his career.

He's achieved the impossible. He allows us to see cruelty in resistance and humanity in a Nazi. Just thinking about this makes me want to weep with joy.

And sadness.

THE FILM CORNER RATING: ***** 5-Stars

Le Silence de la mer (The Silence of the Sea) plays at at the TIFF Bell Lightbox Summer 2017 series "Army of Shadows: The Films of Jean-Pierre Melville". It is also available on a gorgeous Criterion Collection Blu-Ray and DVD that comes complete with a new high-definition digital restoration, with uncompressed monaural soundtrack on the Blu-ray, Melville's first film, the short 24 Hours in the Life of a Clown (1946), a new interview with film scholar Ginette Vincendeau, Code Name Melville (2008), a seventy-six-minute documentary on Melville’s time in the French Resistance and his films about it, Melville Steps Out of the Shadows (2010), a forty-two-minute documentary about Le silence de la mer, an interview with Melville from 1959, a new English subtitle translation, plus a booklet featuring an essay by critic Geoffrey O’Brien and a selection from Rui Nogueira’s 1971 book "Melville on Melville".