The following interview with Terrance Odette is PART TWO of my coverage on the landmark screening of Terrance Odette's HEATER playing at Toronto's TIFF Bell Lightbox in the important Open Vault series July 16 at 6:30pm. For tickets, visit the TIFF website HERE. PART ONE of my HEATER coverage is a review of the film which you can find HERE

Heater (1999)

dir. Terrance Odette

Starring:

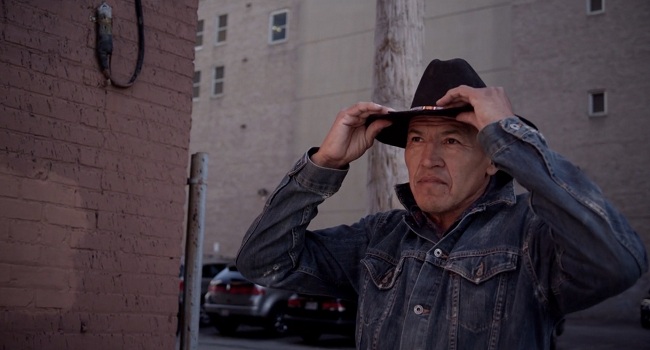

Gary Farmer

Stephen Ouimette

Mauralee Austin

Tina Keeper

Blake Taylor

Joyce Krenz

Sharon Bajer

Martine Friesen

Wayne Niklas

Jan Skene

Jonathan Barrett

****

Interview with

Terrance Odette

By Greg Klymkiw

TWO MOVIE GEEKS

ON SARAH POLLEY, SPIDER-MAN, DON SHEBIB

& HEATER

Terrance Odette: Before we get started, I’ve gotta say one thing to you.

Greg Klymkiw: Yeah?

TO: I fuckin’ loved

Take This Waltz.

GK: Isn’t it fucking great?

TO: You know, I read [insert interchangeable name of film “critic” here]’s review of Sarah Polley’s film, which said the movie sucked and I heard from people I talked to in the film industry and stuff and it’s like, “Ah, it’s a bit of a disappointment” and all that negative stuff.

GK: Fucking morons!

TO: I enjoyed it way more than her first feature film,

Away From Her.

GK: Yeah, and that picture’s certainly no slouch.

TO: Exactly.

GK: Though

Take This Waltz is leaps and bounds ahead, it reminded me of Sarah’s stunning short drama

I Shout Love. Even at that stage of her directorial career, the short signalled the birth of a world-class director. I was convinced then as I am now, that she's going to continually knock us on our collective butt-cheeks.

TO: I was so proud of Sarah when she made

Away From Her, but

Take This Waltz is completely in another dimension – especially considering that the first movie had Alice Munro as a starting point while this one is an original script by Sarah, she’s clearly up there with contemporaries like Andrea Arnold, Kelly Reichardt – the new female Turks of contemporary cinema.

GK: Look, it makes sense to me that Sarah would be considered in that specific pantheon, but I almost feel like she’s jumped well over their heads and moved into a completely different stratosphere. She successfully blends working with so many layers, but when you strip them away, you’re left with a very strong narrative arc that supports all her cool shit, including dollops, or at least nods – albeit skewed – to commercial filmmaking.

TO: I’m looking forward to seeing it again, though I’ll have to wait until I get into Toronto. I didn’t get to see it until its second week which is when it ended in my neck of the woods, but come on! The movie did two weeks in Stony Creek.

GK: Two weeks in Stony Creek for anything that isn’t some pile of shit is astounding.

TO: Oh yeah, good on Mongrel Media for pushing this movie so aggressively.

GK: Yeah, that’s a distribution company with real vision – between Hussain Amarshi and Tom Alexander at the helm, I still hold out some hope for the survival of English-Canadian cinema. “Ephemeral” seems to be a dirty word to those guys which, makes complete sense because they got behind a movie like Sarah’s that is going to have a life well beyond its initial theatrical release. In an ephemeral sense,

Take This Waltz might not reach the adulatory heights of

Away From Her, but it’s so clear that this is the one that IS going to last.

TO: Sarah pushes the edge and it makes me really happy that I can see a movie I love that also teaches me things about the filmmaking process. It’s so sophisticated, so mature.

GK: Unlike, say,

The Amazing Spider-Man which, I recently had the misfortune of seeing – a movie made by this guy, Marc Webb, whose major claim to fame is having directed tons and tons of music videos. The picture has no style, no voice and its very competence gives competence a bad name.

TO: Oh, for sure. I just saw it myself, and boy, did that movie suck.

GK: I think it’s the whole music video thing that drove me craziest – all those stupid montages set to mostly crummy music – Ugh!

TO: That can be a real trap for directors who spend too much time making music videos. Music videos have no content but the song itself – they’re all context. Spike Jonze is one of the few who finds content in the context and is finally, a genuine film artist. Most of those guys work with the best technical people and frankly, they’re good technicians themselves. With

The Amazing Spider-Man, Webb clearly lucked out having great actors and technicians, but only a real artist could have worked through script holes designed to drive a Mack Truck through. I mean sure, it’s a superhero movie so there’s already a layer of implausibility, but that idiotic scene where Peter Parker gets bitten in the first place isn’t even plausible within the implausible superhero world.

GK: That’s unbelievably stupid. I almost threw in the towel and walked out during that scene. They make such a big deal about the high levels of security in that place and when it’s convenient for the filmmakers, they just waltz Peter right into that room. And even when he’s buggering around with things in there, are we supposed to buy that this isn’t sending the place into total lockdown?

TO: That’s right. And I really felt bad because I went to see it with my daughter yesterday for her birthday and all the way through it I kept rolling my eyes and when it was over, she was excitedly and expectantly asking me what I thought and I’m like, “I really loved the acting.” She’s seeing it again today with a bunch of friends – more of a social thing.

GK: Yeah, that’s what made

Titanic or

Sex and the City such hits. They’re not movies, they’re social events.

TO: What I don’t get is why someone didn’t notice at a script stage how interesting the villain was and then do everything in their power to get Peter in his Spidey suit and get down to business instead of all that boring walking around.

GK: Well, you need a director for that - a real director, a real filmmaker. Not some competent, unimaginative hack. Someone needs to be driving the engine right from the start – someone who understands the iconography of

Spider-Man. Sam Raimi got it and he’s without a doubt a real filmmaker with a voice and vision. And speaking of vision and voice, you cut your teeth on music videos, but

Heater is clearly imbued with the very distinctive touch of a true film artist. What was happening that saved you from continuing to rest on the laurels of a lucrative gig?

TO: I really used the music videos to hone certain levels of craft, but I really wanted to work in a narrative tradition. My wife Alicia [Odette] worked as a street nurse in the 90s for an organization in Toronto called Street Health that served the health care needs and advocated for the homeless or what they called the “under-housed” which could be people living in squalid rooming houses or things like that. She had clients from all walks of homelessness – people living in the woods around the Don Valley, on the streets, in all those rooming houses near the drop-in centre which still operates at Dundas and Sherbourne in downtown Toronto. She was one of four nurses working there at that time and one day she came home and the first thing she said was, “This guy tried to sell me a baseboard heater.” She’d get guys trying to sell her stuff at the centre all the time – like steaks – all kinds of crazy stuff. But this was the craziest. Can you imagine a guy wandering around homeless in Toronto during the winter, clutching a brand new baseboard heater that he couldn’t plug in because he’s living on the streets? This was more than enough to inspire me to start writing a script. This is what got the whole thing rolling.

GK: You based this story on events in Toronto, yet as someone who spent the first 33 years of his life in Winnipeg, your movie felt like it couldn't have been set anywhere other than The 'Peg.

TO: Winnipeg was an amazing location and whatever city the movie was set in, it couldn't just be a backdrop, but needed to be as much a character as those in the movie.

GK: Yeah, that speaks to the movie's universal qualities.

TO: It was always so important to me that I tell a story that could be appreciated in any context.

GK: And, frankly, it's so universal, I'd add

anytime.

TO: When it's cold outside, we all need a heater.

GK: Actually, the character Stephen Ouimette plays, the guy with the heater, is a rich and important character, but the movie is really about the character Gary Farmer plays.

TO: That’s because the heater guy had plenty of obstacles to overcome, but I wanted a central character who had the greatest opportunities to grow and change over the course of the film and from the beginning I knew there had to be two men playing off each other and even working as a team – a partnership.

GK: A bit of John Steinbeck in the mix.

TO: Exactly. I used my imagination to create this character and kind of even projected myself through it. I kind of see myself as a bigger person and as I developed the story I was even more convinced he’d be this big lumbering guy. I just thought about what someone like me would do with every bad piece of luck thrown at him.

GK: And then he meets someone worse off than he is.

TO: That’s right. It’s something very, very simple.

GK: And simplicity is what gives you the layers.

TO: Yes, once that simple approach was nailed, I was able to layer-in a character who had an air of inscrutability about him – like he was always thinking his way through stuff or embroiled in deep memories he’d rather forget. In fact, I wrote the script for a white actor and never thought about him in terms of being Native. I imagined the late Maury Chaykin in the role, but he turned it down and when that happened, it dawned on me that Gary Farmer would be great.

GK: And given the neo-realist approach you take from a stylistic standpoint, it’s that very simplicity that really opens up the world to you as a storyteller.

TO: For sure. I was, at the time, heavily inspired by the Abbas Kiarostami trilogy of

Where is the Friend’s House,

Through the Olive Trees and

Life Goes On. His approach is visually more complex than people might give it credit for, but his simple approach was very enlightening for me.

GK: I’ve been listening to the Don Shebib commentary track on the new Blu-ray release of

Goin’ Down the Road and it’s a movie I love a great deal. In fact, when I first saw

Heater, the first thing that popped into my head was Shebib. Though his movie feels improvised or on the fly, it’s really scripted and he gives considerable credit to screenwriter William Fruet’s writing. Because it was so well written, it allowed for a few moments of sidetracking or taking advantage of certain elements that popped up due to exigencies of production. His crew was lean and mean and his shots were pure documentary style – or, if you will, infused with certain elements of neo-realism.

TO: Yeah, it seems he had the same situation I was in – where knowing what you do have and knowing what you don’t have rules the day. There’s no way you can make silk out of a sow’s ear, so why bother trying? Instead you make a really first-rate sow’s ear. Even Kevin Smith’s

Clerks, which is not really a sense of humour I respond to, I was finally able to succumb to - as did so many - because he took what little he had and made it a virtue. It was 16mm, black and white, super-grainy and with that script, it couldn’t help but work. If he’d shot that film in colour, 35mm, with mega-production value, I doubt it would have worked and I especially doubt it would have been a hit. I made so many music videos where I had all the toys – the cranes, the swoops, the dollies, but with

Heater, I knew I wasn’t going to have that, so you make the decision going in what your approach is going to be and make the best movie you can within those parameters. You’ve gotta know what’s in your toolkit. That’s what Shebib did and it’s what I had to do.

GK: One of the things your film shares with Shebib's is a great sense of rhythm - that wonderful, musical poetic aspect of cinema. You had the good fortune to be working with one of Canada's best editors, David Wharnsby.

TO: David's a joy to work with.

GK: Any guy who can cut Sarah Polley's

Away From Her AND Guy Maddin's

Saddest Music in the World is tops in my books. Like all great editors, he's at home with "silent" cuts, but goddamn it, when he makes one of those breathtaking Wharnsby lollapalooza slices, I'm in ecstasy.

Heater has a few moments like that where certain cuts are unbelievably dazzling, but never for the sake of just a cool cut - they're always rooted in both the rhythm AND the narrative.

TO: You're right. Given the form of

Heater, it was always going to be in the cards to employ certain French New Wave-styled cuts.

GK: Shebib went back during editing and filled in a few bits and pieces at the beginning of the film – most of that stuff where Joey and Pete are on the road. In fact, for much of it, his D.O.P. Richard Leiterman wasn’t even available, so he called up his old buddy from film school to shoot. So there he was – Shebib, his two actors and Carroll “Fucking” Ballard.

TO: That’s amazing. It’s interesting that you do have a lot more freedom when you’re making the best sow’s ear you can. During the shoot, I re-shot 25% of

Heater. For example, that scene where Gary drags Stephen across the street – we shot four times over four days until we got it right and like Shebib on

Goin Down the Road, we had no permission or permits to even do this. Or sometimes, being in Winnipeg, we’d get hit with a snowstorm and this would happily force us to come up with stuff to exploit it. And Gary threw in the whole harmonica thing, which was so perfect for the film. And that’s Gary playing.

GK: One of many things I love about

Heater is the look of it. You’ve got Winnipeg, in the winter for one and then you’ve got all the terrible beauty of the fluorescent interiors. I think it’s great that for your first feature you worked with the D.O.P. Arthur Cooper who is one of the best shooters in the country. His hand-held is amazing, his compositions always exquisite and he’s a true master of light. Where did you first hook up with him?

TO: I was producing a series for Vision TV and Arthur was hired as a camera operator. We hit it off almost immediately and we’d always watch a whole bunch of movies together and really discovered a shared sensibility. It was an extremely close friendship, rooted on my end in a deep respect for his artistry. At one point, I mentioned that I wanted to make a short film and he immediately offered to shoot it. He and I continued this collaboration on my rock videos with me. We worked together almost exclusively and for a very long time. When it came time to do

Heater, I gave him the script and we never stopped talking about it. As the movie came closer to reality, we made the decision that our sow’s ear would be shot in 35mm to allow us the flexibility of using available light for night exteriors and anywhere we wanted to capture a natural look, but without the cost and mobility burden of lights and generators. Arthur really shone here. I had a specific look in mind based on what we had available to us and he delivered the goods and then some.

GK: You guys must have developed a keen shorthand.

TO: Oh yeah, I trusted him, he trusted me. You have to remember we were working in a pre-digital age – with film, on film, no video assist and a 48-hour delay in seeing rushes, so it was a classic director-D.O.P. relationship. I put all my faith in him and it always paid off. On

Heater we had limited resources and only used what we absolutely needed to get the shots to recreate the terrible beauty of the world these guys live in.

GK: Yeah, that opening is so stunning with Gary sitting there in the welfare office while the bureaucrat putters about and those fluorescent lights casting that horrendous harsh glow over everything.

TO: That’s it. When we needed fluorescent lights, that’s what we went for and Arthur would pop the Kino bulbs in whenever we could.

GK: Gary Farmer is so astounding in that first scene that it’s like we can’t ever take our eyes off him. I can’t imagine

Heater looking any differently than it does and I certainly can’t imagine it without Gary.

TO: Yeah, and it’s funny, when I offered it to him, he wasn’t really interested in the script, but wanted to meet me anyway. He was, as it turned out, very interested in the character, so as the script developed, he got happier and happier with it until one day he revealed a tiny smile and just said [TO in a superb Gary Farmer voice], “Yeah, put my name down.” The agreement we made from the start was that I’d never specifically write anything dealing with the character being Aboriginal. I was going to write a guy living on the street. Gary would add any Aboriginal stuff when necessary. If there was stuff I wrote that Gary felt needed some culturally specific elements, he and I would discuss it, but I’d ultimately defer to him on those elements. It’s these additional touches that make it more complex.

GK: What were the differences in acting styles between Gary and Stephen? Gary’s a veteran screen actor and Stephen, though he’s done plenty of film, comes from a classical theatre tradition.

TO: I think Gary Farmer played Gary Farmer and that’s what Gary Farmer does the best. I think Stephen is more of a character actor. At the time of shooting, Gary really understood that acting on film was about the face, about the gesture, about the reactive qualities and not about what you say. And Stephen is such a great actor and brings his own set of tools that occasionally all I needed to do was ask him to bring the levels down and he delivered beautifully. Directing these two different, brilliant men was always challenging and invigorating.

GK: Surely those guys had individual skills they could bring to each other. The chemistry between them is astounding.

TO: That’s probably because I was making my first feature and smart enough to back off and let them be together. They were always having fun with each other. Gary is so hilarious on and off screen with his Buster Keaton-like deadpan and on more than one occasion I saw him amiably pushing Stephen’s buttons. Oh, and if anyone requires an actor to pee – on camera, on command – Farmer’s the man. We did five takes in a row of that peeing scene and Gary, with no complaints, conjured it up every single time. And the other thing is that the three of us just had a wonderful camaraderie. The bit with the hair dryer was one where most films would deal with in post-production, but I explained we didn’t have the money or time to fuss with stuff like that in post and the two of them were, “Yeah, let’s do it!!!” The bottom line is that I was always happy to step back and give them the space to create their friendship.

GK: On

Torn Curtain, Hitchcock loathed working with Paul Newman because he’d continually be method acting to distraction. Would you say Ouimette’s a method actor?

TO: Stephen keeps his method to himself. I’m sure it’s there, but he’s really that perfect balance of method actor and that thing Olivier said to Dustin Hoffman on

Marathon Man: “Just act!” Not to take anything away from Gary, but he’s a different entity. He brings so much of himself to his roles.

GK: Well hell, that’s a good chunk of film history there, anyway. The other “Gary”, Gary Cooper, was pretty much always Gary Cooper, as was John Wayne. Their “method” was to bring themselves to every role and it’s great acting – pure and simple. When people say they can’t act, or that they’re “just” being themselves, I’m compelled to kill them. My innate humanity and compassion prevents me from doing so.

TO: Well yeah, think about Bogart. He sang very few notes, but the notes he sang are so wonderful, we want to see them again and again. Gary’s the same. He’s a great actor.

GK: Gary has real star quality. Stephen too. I always refer to certain actors as leading men in character roles. Gene Hackman always had that quality.

TO: When Gary and Stephen are together, it’s screen magic. Those two carry the film. When you watch the movie you’re engaged by both of them. I love the scene in the end involving the two of them and the whole business of the smokes. The scene is written in a very specific way, and the two of them go through the actions, but I could never have, in my wildest dreams ever imagined how wonderfully it would be performed. And the very humanity they bring to this scene and, in fact, the whole movie is what towers above what’s on the page.

GK: Don’t be modest. It WAS on the page. That’s what counts. What’s on the page is the springboard to vault everyone into the magic that is movies and the magic of your film.

TO: Well, it’s interesting. I remember meeting someone from Miramax who told me that the scene in the welfare office made her cry and I was like, “I’m not trying to make people cry, I’m just trying to be honest.”

GK: Look, what’s important about the film is that it’s rife with moments of heartbreaking humanity and – Hello! – We’ve got 90 potentially depressing minutes with two homeless guys, but amidst the tears and the bleakness of the landscape, their humanity DOES shine through and I’d also say, the movie has a lot of natural humour that comes from that humanity. It’s like Shebib’s

Goin’ Down the Road – like, Hello Again! – You’ve got two loser drifters from the Maritimes looking for a better life in the Big Smoke and ultimately they face rejection, poverty and are driven to committing an act that they’d normally never imagine doing in even their wildest dreams. But goddamn it, Joey and Pete are funny. No matter what depths one drags one's characters down to, humour always plays an important role in beefing up the humanity – on-screen and in life.

TO: Humour, some of it black, was already there, but these two actors were able to breathe such life into their roles that they’re responsible to some extent for adding that layer to the film. I love that moment in the donut shop – you probably know that joint since you’re from Winnipeg – it really is a crack hangout.

GK: I have dined on many a stale donut and rancid coffee in that very establishment.

TO: Yeah, and when Stephen steals the money, it IS funny.

GK: A most tempting action in places like that.

TO: Yeah, it’s finding those little moments that make all the difference. What I learned most from my wife Alicia was that the dignity of every human – as simple and clichéd as that sounds – is inherent in all those people and they shouldn’t have to lose that dignity. I think when a character is allowed to laugh at themselves or their situation it’s all part of allowing them humanity and, in turn, dignity.

GK: I’ve heard tales about Mr. Ouimette’s personal hygiene during the shoot.

TO: I can say he did not take a bath for the entire period of shooting. This, I believe personally disgusted him and I truly believe he wanted to take a bath. Maybe he even did on his days off, but I have no means to prove it.

The following interview with Terrance Odette was PART TWO of my coverage on the landmark screening of Terrance Odette's HEATER playing at Toronto's TIFF Bell Lightbox in the important Open Vault series July 16 at 6:30pm. For tickets, visit the TIFF website HERE. PART ONE of my HEATER coverage is a review of the film which you can find HERE